How My Heart Grew - Part 3

learning to really love the least of these

Release and Gather is in its ninth month now, and I think you’ll love what we have in store for February. Next week, we’ll have our February Collection, and y’all—I have been reading and cooking up a storm! Get ready for some great recommendations.

Then you’ll read the story of a local business owner and his resilience in adversity. I sat down with him a couple of weeks ago to learn how the theme of “release and gather” fits into his story, and I’m sure you’ll be inspired by his journey.

At the end of the month, I’ll post a round-up of what was published in Winter 2023. As with past round-ups, you’ll see a list of links to all posts with a short quote from each so you can check out whatever piques your interest. These posts also include a list of Substacks I’ve discovered and why I’m enjoying them—in case you need some fresh reads! Check out some of the past digests to get a feel for what’s to come.

Quarterly Round-up: Summer 2022

Finally, welcome to several new subscribers this week: Jilson, Ibrahim, Sohrab, JW, Vijay, Diane, William, Nolan, Donna, and Adnan. Thanks for joining us! I hope you’ll find something to inspire you to dream big dreams or challenge you to consider a new perspective—or both! I invite you to join some of the best discussions on Substack in the comments section of each post.

And now for our feature presentation!

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this How My Heart Grew series, I shared two stories of challenging seasons and situations that forced me to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

I’ve mentioned this before, but I want to share it again for newcomers:

This story involves my Christian faith—a faith I understand not all readers ascribe to. I believe the lessons, however, are universal. Whatever your spiritual faith—and maybe that’s none—I hope you’ll read on.

Will You Come Tomorrow?

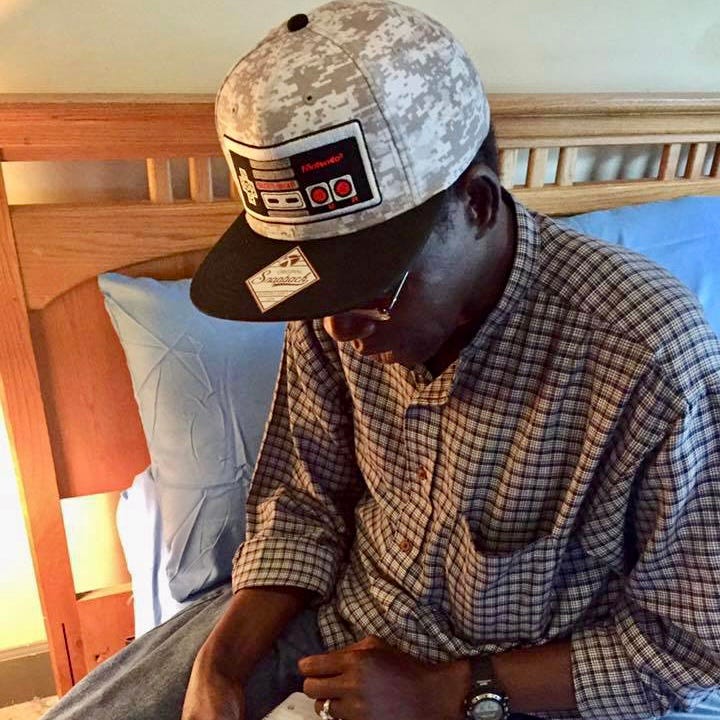

I went by Sam's place three different times to deliver a few items, but he wasn’t home. We’d recently met Sam while serving breakfast under the Mississippi River Bridge with The LOT Project, a nonprofit homeless ministry our good friends Billy and Erin started several years ago to love and help meet the needs of homeless people in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. With the help of The LOT Project, Sam found a job and began working then secured housing for himself.

I had collected items for his new apartment, and during my final delivery attempt, I walked past a young man sitting on the steps that led up to Sam's place. Smoking his cigarette with his earbuds engaged, he returned my greeting with a distracted, “Hello,” as he stared at his phone screen.

An agitated man, the resident of the apartment below Sam’s, was sitting outside his front door talking to the man on the steps a few feet away. As I walked toward my vehicle, I felt the urge to go back to him.

I don’t wanna, God. This is not the best neighborhood, it’s getting late, and I just want to get in my car and go home. Please? Can we not do this today?

I’d been through this before. Now, this might be a little too woo-woo for you if you’ve not experienced it, but there are times when I feel God nudging me to speak to someone and I just can’t ignore it. All I know is that I can’t walk away until it’s done or I will regret it. Oftentimes I don’t even know what I’m going to say until I open my mouth. Don’t worry—I’m not prone to telling people to “turn or burn” or that the world is ending in five days.1

“He looks ill. Could I pray for him?” I asked the young man as I walked toward them.

“Excuse me?” The man’s eyebrows shot up and eyes widened, a contrast against his dark skin.

“I said he looks as though he doesn't feel well. Would it be okay if I pray for him?”

“If you feel so moved, by all means,” he replied with an accent I couldn’t place. “He's really bad depressed right now—just going through a really hard time.”

I knelt by the older man and inhaled the scent of fermentation seeping from his pores and looked into his yellowed and bloodshot eyes as I took his folded hands from his lap. I held them in mine and prayed in the name of Jesus that the weight of this depression would be lifted from him.

It’s worth noting that I don’t go around praying in public like that. I prefer to offer up my simple prayers behind closed doors—you know, where people won’t judge me as being one of those religious fanatics. I was completely out of my comfort zone in more ways than one.

When I finished, the tired, sad man was rocking slightly, his face lifted upward and his eyes closed as his lips moved. His robe hung on his frame, skin and bones from lack of food and abundance of drink.

Through a brief exchange, the man on the stairs told me that the sad man's name was Lamin. Having lost his hearing because of a fever he contracted in Africa when he was 9 years old, Lamin was deaf but could read lips and speak English.

“He was born in 1965,” replied the young man when I asked his age. “It's all the drinking that makes him look so old.”

He went on to explain that Lamin's family had moved away—his mother and his brother. He’d done okay until a year and a half ago when his wife left him.

“I came over to bring him a new card.” He waved a paper and produced a VISA card. “People around here steal all his things.”

Lamin kept saying “brother” and pointing to him, but the younger man explained, “I’m just a friend. I try to look out for him.”

“You will come tomorrow?” Lamin slurred as he looked at me.

I paused for a second. “Yes. Yes, I will.”

“What time? Show me the time,” he motioned to my phone.

I set my alarm to 5:15 p.m. and showed it to him. “Tomorrow,” I said as he watched my lips.

“I will be sober,” he said, and the young man shook his head as though that would be a miracle. Lamin brushed his palms together as if to say, “That’s it. I’m done for good.”

The young man continued to shake his head.

Lamin grew solemn again and began to weep, “I promise I won’t be bad.”

I looked into his eyes and told him I would see him at 5:15 tomorrow. Then I patted his shoulder before I left.

The next day, I went to see Lamin as I had promised. When he looked up and saw me, his mouth flew open as he breathed in, “Ahhhhh! I am an alcoholic. I want to stop. Please help me to stop.”

We talked some, and I told him I would try to find some help for him. He said, “Rehab. I will go. I want to go.”

Waiting for Deliverance

The next morning, Mike and I pulled into the parking lot of Lamin's apartment building at 8 a.m. Even though we were half an hour early, Lamin waited expectantly on the sidewalk and jumped up when he saw me step out of the car. Neighbors and the property maintenance worker stood around him, making sure he had everything—his bag, toiletries, and his “papers.”

Lamin was ready to do what he told me he wanted to do. He was ready to get clean. He had to get clean. His life depended on it. He crumpled to the sidewalk as weakness washed over him. Tiny beads of sweat formed from the pores on his face.

“Dat all dat gin comin’ out,” remarked one neighbor. “I hope he stay in, but you just wait 'til he get dat check at the first of the month. He gone be checking hisself outta dat place and gone spend up that whole check just like he always do. He always spend it up on dat drink, and people be takin’ the rest ‘fore the rent man come round.”

His longtime neighbors wanted to have hope—there was a sparkle of it in their eyes—but they dared not speak it. They told me stories of Lamin drinking so much that he passed out in the parking lot of the store next door.

“He was just laying there, the antses just crawlin’ all over him. An’ one time the ambuhlance had to come pick him up in dat same parking lot.”

They said he wasn't always like that, but the last five to six months had been bad. He had done nothing but drink. I assured them that I planned to remain involved to encourage Lamin and help hold him accountable throughout the process. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

Mike started the car, and I walked Lamin over to it. He tried to get into the back seat, but I insisted he sit in the front where the AC would blow on his face.

“Thank you. Thank you,” he whispered as he eased into the seat.

Someone called, “Wait...let me get his Bible,” then returned with a small, leather-bound King James version with initials stamped on it (not his initials).

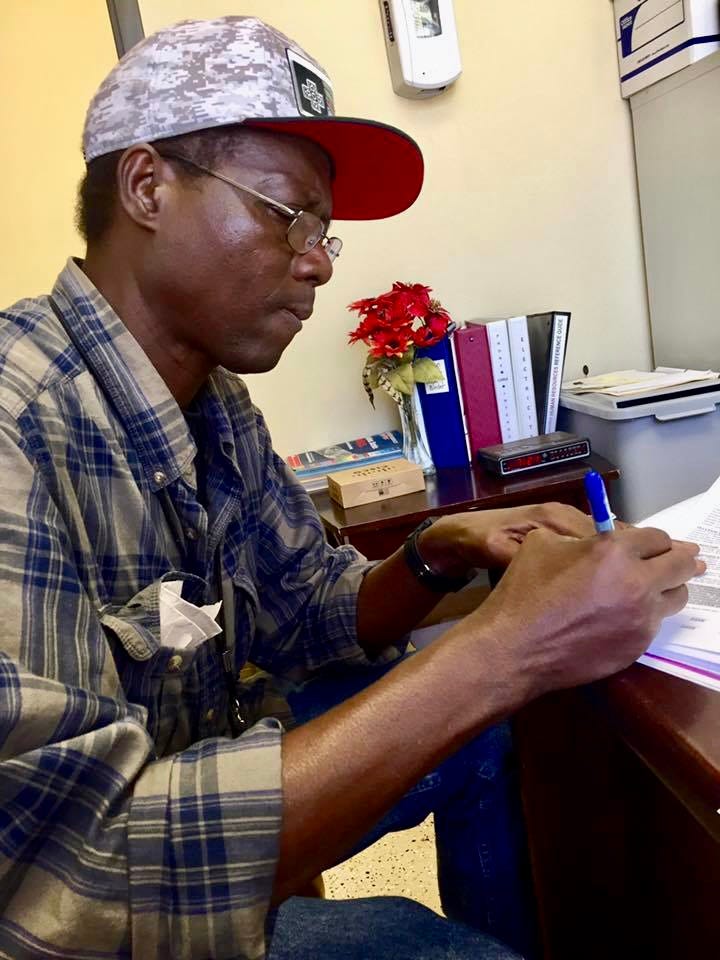

When we arrived at the Salvation Army, we drove around back to “Intake” as I’d been instructed when I spoke to the director the previous day. The parking lot attendant waved me into a spot then I helped Lamin from the car and directed him into the small foyer that had a few simple chairs and a large reception window where two men stood. The director, Daniel, asked Lamin if he had a driver's license or a Medicaid card.

“No, it was stolen. Here, this is all I have—my Social Security.” He pulled a worn, green debit card from the pocket of the pants I'd seen him wearing for four days now.

“Where are your papers, Lamin?” I asked then typed into my phone when he couldn't read my lips.

“They are all there in my bag. All of my papers are there.”

I opened his overnight bag and pulled a plastic zippered bag from it as Daniel came around to the foyer. He looked through the stack of papers as he spoke.

“He's bad off—I could tell that while I was watching him get out of the car. And I can smell it on him. You can tell he's in pain. He's not in control of his life right now. The alcohol's in control—it's master over him and he has no choice but to obey. When you go so many months drinking like that, it does things to the body. He needs intensive treatment where the control can be broken, either through the treatment or through deliverance. Me, I believe it takes deliverance.”

Daniel finally located a paper he could use for identification and explained they were going to contact a local hospital that had a detox center.

When he walked back to the office to get the process started, I knelt by Lamin. “They are going to help you.”

“Okay. How long? Maybe like two months?” he asked.

“I don't know. Maybe one to two months.” I typed on my phone.

“Will you come to visit me?”

“When they tell me I can visit, I will come.”

I turned to Dan, “He doesn't have any family here—should I leave my number with him?”

Dan took my name and number and assured me they would call to update me.

Lamin read my lips and nodded as I assured him, “You're going to be okay.”

I held my hands out and he took them so I could pray for him. All office noises stopped as I called on God, our Deliverer, to be with Lamin and remove from him the desire to drink.

“Thank you. Thank you.” Lamin nodded as tears spilled from his eyes. He turned to Mike and again said, “Thank you,” as he extended his hand. Mike shook it, and then I gave him a hug.

I looked into his eyes one more time, and for the first time, I saw him smile.

Connection in the Waiting

I wish I could say everything was easy after that, but it wasn’t. Many rehabilitation programs are willing to take on new clients. Almost zero are willing to accept new clients who are deaf but do not know sign language. Most clinics knew how to get an interpreter, but the ones I spoke to weren't sure they could find the right one for him.

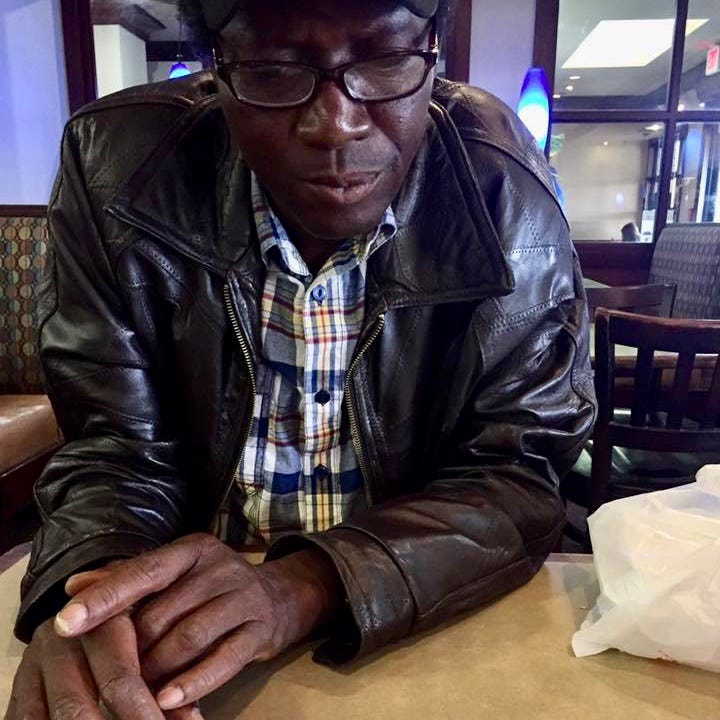

So I continued my role as Lamin’s advocate. He was moved from detox to another facility, and he made sure his social workers kept me updated on his location. Less than a week into his stay at the new facility, his social worker contacted me to let me know he was sent to the hospital with chest pains. I took my lunch break at work and went over.

After locating his room, I settled onto the edge of Lamin's bed, and he told me he would have “a surgery” that afternoon. The papers he pulled from his bedside table described and illustrated exactly what would happen during the procedure—a heart catheterization. He grew very excited as he told me how they forced him into the hospital to look at his heart even though he insisted nothing was wrong with it.

Eventually, however, they convinced him that the “burning from the front allllllll the way to the back” needed to be investigated. So now he waited, counting down the hours, but assuring me that he was not nervous. It was during this wait that Lamin finally told me his story. And what a story!

Lamin was born in Sierra Leone, Africa on New Year's Day 1965. With a big grin he joked, “The whole world was celebrating when I was born!”

Some problems arose because his father was a citizen of neighboring Liberia, and the family had to relocate there. When he was nine years old, Lamin contracted yellow fever and was sick for three months before recovering. He remembered his mother thought he was joking when he told her he couldn't hear. This was the beginning of life without his sense of hearing.

In 2004, fleeing years of civil war in Liberia, Lamin's family sought refuge in the United States with the hope of a better life. “We came here—17 total in my family. 17 came to New Orleans.” Now his family had grown to 24 and lived in multiple states, including New Jersey, Texas, Georgia, New York, and Washington. As he told his story, I quickly jotted down the names of his family and what states he said they lived in.

The story was interrupted as someone came to take him for his procedure. He asked me to pray with him before he went in for the procedure, and I wrote “Okay, I’m going to pray now. What religion are you?”

I had not really asked him that before, but I thought maybe I should ask just in case he had a different kind of prayer in mind.

“I am Christian,” he said with great seriousness. “I believe in God the Father and Christ Jesus.”

“Me, too.” He read my lips as I spoke. I took his hands as we bowed our heads. My words were lost on his deaf ears, but not on his heart. As I prayed aloud, I heard Lamin whispering his own prayer, and when I was done I squeezed his hands and opened my eyes. A few seconds later he opened his, too. “Father God will be with me.”

“Yes, He will,” I assured him.

The heart cath revealed some blockages, but the doctor insisted the arteries were too small to put in stents, and he wasn’t a candidate for bypass surgery. So they kept him in the hospital for a few more days with medication to help keep his other arteries clear. Lamin was not in great health.

After another week of relentlessly pursuing all avenues, I finally found a rehabilitation program that would take Lamin. His case was unprecedented, but because he could speak and read, the director, Emily, was willing to give it a shot. Lamin thrived there for three months.

The wonderful staff worked with Lamin and helped him stay sober. Mike and I visited routinely, taking him to doctor’s appointments and making sure he had his medication. During that time, I also became well acquainted with the process for replacing a Social Security card, transit system card, state identification, Medicaid card, food stamp card, and debit card. In all the shuffling around from facility to facility, Lamin lost all his documents and nearly all that he owned. But he had his life and plenty of resources to help him stay sober.

During our visits, Lamin told us stories of his family and life in Liberia. We spoke more of his brothers, sister, and mother. I learned he had a daughter and wanted more than anything to see her again.

After three months, Lamin signed paperwork to move into sober living. We had also been trying to locate his mother during his time in rehab. He’d mentioned that one of his brothers was a professor in a particular state, and enough sleuthing landed me an email address. I sent a message letting him know that Lamin wanted to be reunited with some of his family if possible. The next day, his mother called me. She was such a joy to talk to, and she couldn’t wait to hear the voice of her firstborn child.

I told her I would visit Lamin the next day and have him call her. Lamin couldn’t hear his mother, but she could hear him speaking to her. I acted as his ears, writing her replies in his notebook. There were many tears that day.

Deliverance

Unfortunately, there would be many more tears in the weeks and months to come. Lamin relapsed and had to leave his apartment. He went to the hospital for chest pains, then was admitted to detox, and then to yet another facility. This cycle continued over and over. We’d get occasional calls about him, but then we didn’t hear from him for many months.

The next call I received was from a case worker at the local hospital he’d been to a number of times. I was the only contact they had on file, and they needed to reach his next of kin. It seemed that Lamin’s days were nearly done. I asked if he was awake. I didn’t want him to be alone if he was.

“No.” She paused before she continued, “He’s…he’s on life support.”

It was a blow, and my heart was crushed. I emailed the brother I had originally contacted to find Lamin’s mother. Within the hour he called me. He’d called his mother, and she had, in turn, called Lamin’s sister, the only family member near the hospital. I gave the brother the number for the hospital and the person to ask for, and he thanked me profusely, telling me he would keep me updated.

Nine days later, Lamin was delivered from his addiction. His mother had flown in and spent time with him, and in the end they did not have to make the decision to remove him from life support. His body took its rest on its own. His battle was over.

Nearly a year before his deliverance when we were still trying to get Lamin admitted to a program, I read this passage and shared it with him:

This I recall to my mind, therefore I have hope. The LORD'S lovingkindnesses indeed never cease, for His compassions never fail. They are new every morning; Great is Your faithfulness. “The LORD is my portion,” says my soul, “Therefore I have hope in Him.” The LORD is good to those who wait for Him, to the person who seeks Him. It is good that he waits silently for the salvation of the LORD.2

That word “salvation” means rescue: deliverance, help, safety, salvation, victory.3

Lamin and I often spoke of how God would deliver him from addiction. We specifically read Psalm 18 and 26 together—well, he would read while I would drive all over Baton Rouge to his many appointments!

Deliverance.

We prayed and waited for Lamin to be delivered from his addiction, and on that day those prayers were answered. Not in the way we wanted or expected, no. But he was rescued. He is free from his mental, emotional, and physical suffering. He is in the presence of His loving Father and Savior.

A couple of weeks after we met, Lamin told me that I was sent to him by God. He was sure of it, he said, as he gave me a copy of an AA meditation he had read:

Wherever there is true fellowship and love between people, God's spirit is always there as the Divine Third. In all human relationships, the Divine Spirit is what brings them together. When a life is changed through the channel of another person, it is God, the Divine Third, who always makes the change, using the person as a means. The moving power behind all spiritual things, all personal relationships between people is God, the Divine Third, who is always there. No personal relationships can be entirely right without the presence of God's spirit.

I do believe our friendship was Divinely appointed. Meeting Lamin changed my heart toward those in the grip of addiction, and what a gift that was because a year after meeting him, my son would begin his own addiction journey.4

Lamin was finally delivered, and I know I will see my friend again one day. For that, I am glad.

“Turn or burn” aka one of the seven habits of highly annoying Christians.

Lamentations 3:21-26, The Holy Bible.

Strong’s Hebrew Lexicon Number H8668.

As someone who has worked in the homelessness space and also spent most of my life around the edges of church culture, I appreciate the pragmatic way in which you approach these relationships and urgings from God. In my experience, church people love to serve “the least of these” in theory, but not so much in reality. I recognize it’s not easy or convenient to pursue these relationships, and I appreciate you sharing your experience.

Holly, What courage you have. Your words brought me to tears. Thank you for sharing your story and Lamin's.